Notes on Being Old, Poor, and Gay

Les K. Wright

When I was one of the disaffected youth of the 1960s Bob Dylan spoke directly to me through his music. Fifty years later “Like a Rolling Stone” still speaks to me personally. When I was young the tone of righteous anger resonated for our generation. Wasn’t it misplaced trust in American values, preached but not practiced, when Dylan sang, “Ain’t it hard when you discovered that / He really wasn’t where it’s at / After he took from you everything he could steal?” As my fellow hippies later abandoned their ideals for yuppified material success, I found I had become an outsider— “How does it feel, how does it feel? / To be without a home / Like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone?” As things got harder along my journey through life I came to points where I didn’t “seem so proud / About having to scrounge [my] next meal.” And here are the lines that I took most to heart, and still do—“When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose / You’re invisible now; you’ve got no secrets to conceal.”

When the rich and powerful take everything away from the weak and poor, when they have taken “from you everything [they] could steal,” the weak and poor become dangerous. They rise up in anger. They have nothing to lose. I eventually realized the rich and powerful were concealing plenty of secrets.

In an opinion essay in Newsweek union railroad worker Charles Stallworth wrote, “the elites have stopped hiding their hatred of the working class.” I come from the working class. All my “fancy degrees,” which Stallworth says, the overeducated elites have in abundance, did nothing to lift me out of the economic reality of my blue-collar roots. As a close personal friend and colleague used to say, “We were trained to appreciate all the beautiful things we would never be able to afford.” As my academic mentor at UC Berkeley told me as I approached my Ph.D. graduation, I would never find a job in academia, but I would have the adornment of my education. (He frequently complained his salary at a public university was not enough to let him summer in Italy every year. His parents subsidized this privilege.)

I now see myself as a romantic incarnation of the poor bohemian scholar. (Poverty is romantic only in literature).I adorn my mind with beautiful, high-minded, sublimely inflected thoughts and live in a low-income apartment I’ve appointed with tasteful, mostly cheap knock-off furnishings.

In 2023 the HRC reported in “Understanding Poverty in the LGBTQ+ Community” that more than one in five of all LGBTQ+ adults currently live in poverty, a percentage notably greater than our straight cisgender counterparts. The more socially marginalized the queer individual is–on the spectrum from gay, white, cisgender men (12%) to transgender Latinx adults (48%) — the greater the percentage of us live in poverty. Older LGBTQ+ people experience poverty at even higher rates.

Those of us who grew up in lower-class and working-class families tend to continue to live in poverty in our adult lives. My parents’ buying power remained higher than mine with my Ph.D. ever was. They both earned a high school diploma. I was the first in my family to attend college. My parents bought their first house when they were 38. I have never been able to afford to buy a house. Until the age of forty I had been either a struggling student or made ends meet through survival jobs. Through scholarships, fellowships, and part-time work (sometimes I worked two part-time jobs while being a fulltime student) I was able to graduate PhD without a penny of student loan debt. My survival jobs included desk clerk, retail clerk, office temp, freelance editor and translator, tutor, and part-time teacher. I am both thankful and astounded that in the 1970s and 1980s it had been possible for me to afford to live in San Francisco on a survival job and with roommates.

Since those days, when gay men and lesbians could be out of the closet and began to have access to more middle- and upper middle-class careers and job security, the economic structure of the United States has changed profoundly. Feudal capitalism has now ended social mobility. Access to career jobs still requires academic degrees. But the transformation of higher education into an endlessly more costly for-profit business enterprise and the collusion of the banking industry to force students into student loan debt that condemns them to a lifetime of debt. Add to this the ever escalating cost of living, from rent or mortgage to the price of food, and we arrive at today’s dire situation. The working class is now the working poor class. Retirement pensions and health insurance are no longer part of the employment package. The American Dream has become a cruel illusion. The younger generations now expect they will never be able to retire and have ceased to plan for it. The gap between rich and poor in our current Second Gilded Age (or Third Gilded Age, according to historians who see the 1920s as the Second Golden Age) has brought us to the edge of Germany in the early 1930s, Russia in the 1900s and 1910s, and surpassed our own original Gilded Age of the 1880s and 1890s. As I write today, the Trump Reign of Terror began just one week ago. Among other things, the economic fate of all of us poor queer people, let alone the entire 99%, is likely to reduce the American socio-economic landscape to rubble.

Queer people, on average, have higher rates of under- and unemployment. We find work in low-paying fields. Fully 40% of us work in restaurants and food services, hospitals, K-12 education, and retail. Despite advances in equality we continue to face discrimination.

This research was collected from data gathered through the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System by Lee Badgett and Bianca Wilson. I met Lee 35 years ago at a conference we both attended as graduate students. She presented a paper demonstrating that gay affluence is a myth. Looking back decades later, I note that Lee’s elite education, culminating with a doctorate in economics, led her to an exemplary academic career. My public university education and doctorate in the humanities left me struggling in a very low-paying teaching position. My published research in bear history did not open any doors to career advancement.

I want to tease out three strands of how I stumbled on the path that education was supposed to lead me out of poverty. The first was my choice to pursue the humanities. In 1971 when I was a freshman I majored in Comparative Literature (German and Russian). At that time a freshly minted PhD with this skill set was rare and highly employable. By the time I finished my doctorate, having taken time off along the way—two years due to late-stage alcoholism, two years exploring other career options, two years of AIDS-related illness and housing instability—the Cold War had ended. The Berlin Wall had fallen. And the Soviet Union had collapsed. What had been strategic languages for American military interests were no longer needed. Both languages stopped being taught in American high schools. Colleges and universities shut down their German and Russian Departments. In the jungle of supply and demand the skill set of people like me was now a booby prize. The Germans finesse this choice of major as an Orchideenfach—an “orchid major”—pretty to look at, but of no practical value.

Secondly, to land a tenure-track job in an exotic field, one needed an academic pedigree, a Ph.D. from an Ivy League school or a major research university. I earned my degrees at self-styled “public Ivies.” My impressive academic training did not include the professional and informal social connections that a “hothouse” academic like me needed to get hired. When I began moving in academic circles I learned that the deck is stacked against working-class academics. American meritocracy is a myth that hides the reality of upper middle-class entitlement and privilege. Although no one would ever say it, we blue-collar academics are often seen as interlopers attempting to rise above our station.

Instead of playing the game—writing my dissertation on a fashionable research topic–I let my passion guide my research interests. I attempted to write about gay male literature in the age of AIDS. Queer Studies had not yet established itself. Indeed, my academic mentors had all cautioned me against doing gay work before I was tenured somewhere. My project was overly ambitious. The literary critical tools necessary for what I had proposed to do had not yet been developed. I was no genius scholar. Most of the literature I examined were books published by small gay presses. This further ghettoized my work to the scope of what German scholars call Trivialliteratur, roughly what Americans call “pulp fiction.” Ironically, contemporary cultural studies is obsessed with such artifacts of pop culture.

My passion for gay studies eventually found a home in gay history. I found my niche as a grassroots historian documenting and publishing bear history. By that time there were scores of positions to teach queer literary theory and history. But my degree was not in either field. Even as other trail-blazing queer historians had found their way into permanent academic posts, bear history remains to this day a marginalized subfield.

In a recent conversation with Perry Brass (a writer and a founder of the GLF) the subject of fame and fortune among our peers came up. In the course of my professional career I had never paid attention to my where my peers’ work was taking them. Today I see how dramatically our fortunes diverged. As I put it to Perry, I didn’t understand why our fairy godmother had not waved her magic wand over me, bestowing fame or fortune as she had with so many of my peers. Many of my contemporaries are enjoying retirement in comfort, pursuing private dreams.

Thirdly, when Wall Street and Madison Avenue realized gay men and lesbians were an untapped market, gay men suddenly became “well-to-do, cosmopolitan, and voraciously consumeristic” in the dream world of advertising. In Nathan McDermott’s article “The Myth of Gay Affluence,” he debunks the “pernicious insinuation” that gays and lesbians are one of the wealthiest demographics in the United States. Our purchasing power (real or fancied) helped to mainstream queer people. This consumer capitalist strategy used the dreamworld of advertising to co-opt gay identity succeeded in selling a queer version of the American Dream back to us. Sexual self-objectification, physical desirability seen in others, and conspicuous consumption have become the determiners of value within the gay community.

Our consumer consumption culture has seduced many bourgeois gay men into believing they can buy their way into middle-class respectability through conspicuous consumption. Advertising imbues products into status symbols that magically transform the purchaser into high social status. It has particular appeal to masking internalized homophobia behind the illusion of bourgeois respectability. “Trolls” and poor queers are largely invisible, even in the gay community. Elderly queers are even more invisible.

In American culture, poor, old people are often considered unnecessary burdens on society. Some powerful elites have “rebranded” Social Security pensions, which everyone pays for during their working years, as an “entitlement.” Such entitlements are viewed by these elites as undeserved welfare and a drain of public money. In Trump’s America Republicans are engineering their program to force poor old people to be left in the streets to die. One week into Trump’s Reign of Terror he has issued and continues to issue a blizzard of unconstitutional Executive Orders that will hasten this extermination program.

And, fourthly, as an aside, the eruption of the AIDS epidemic re-stigmatized gay men in the 1980s, undoing some of the progress toward assimilation and legal equality in the aftermath of Stonewall.

In the immediate aftermath of the Stonewall riots several gay men organized the Gay Liberation Front. The stated purpose of the GLF was “the liberation of homosexual men and women in this society from the basic three-pronged oppression [societal, legal/quasi-political, psychological] they suffer.” As part of the larger civil rights and cultural revolutionary politics of the time (Black Liberation, feminism, anti-Vietnam War pacifism) their goal was a radical transformation of society for the betterment of everyone.

Concurrent with this was the gay civil rights movement, led by Frank Kameny, to integrate gay men and lesbians, long a stigmatized minority, into mainstream American society. The abandonment of GLF ideals was exemplified in the history of the Mattachine Society. Cofounded in Los Angeles by communist Harry Hay, the organization sought to change society. When the vision of gay men as deserving of civil rights because they are the same as straight people, except for what they do in bed, its radical politics were replaced with assimilationist equal rights politics. Hay was expelled from the Mattachine Society, Frank Kameny founded the Washington, DC chapter of the Mattachine Society, and revisionist historians removed the radical roots in gay liberation, elevating Frank Kameny as a star pioneer.

Whether having full-blown AIDS or merely suspected of having it, gay men were often abandoned by our families, fired from our jobs, evicted from our homes, were turned away by hospitals and funeral parlors. This added another layer of poverty, which many of us PWAs (persons with AIDS) did not recover from. Many of us long-term survivors of AIDS—we never planned for a retirement we never expected to see–now find ourselves in unanticipated poverty in old age.

My memoir Resilience has been compared to Lars Eighner’s memoir. He wrote eloquently about being homeless. His downward spiral began when a combination of illness and challenges caused by him being gay left him unable to finish his academic training. He later quit his job due to a dispute with a supervisor. After that he was turned away from every job he applied for. In spite of all this, Eighner managed to write Travels with Lizbeth, which was published by St. Martin’s Press. It was noticed widely, appeared on the cover of the New York Times Book Review, and was even on the New York Times bestseller list. He even found a loyal, loving, long-term partner. His fairy godmother waved her wand over him.

My own life has followed a similar path. I gave up my effort to find a loyal life partner after both of my last two long-term partners betrayed me, getting involved with another man behind my back and leaving me high and dry. I have come close to homelessness, luckily landing on friends’ sofas rather than a park bench or doorway. The fear of homelessness, however, never completely leaves me. As Eighner told a reporter, “I’m pretty much constantly in terror of going back on the streets. It’s like being on a glass staircase. No matter how far up I get, when I look down, I see all the way to the bottom.

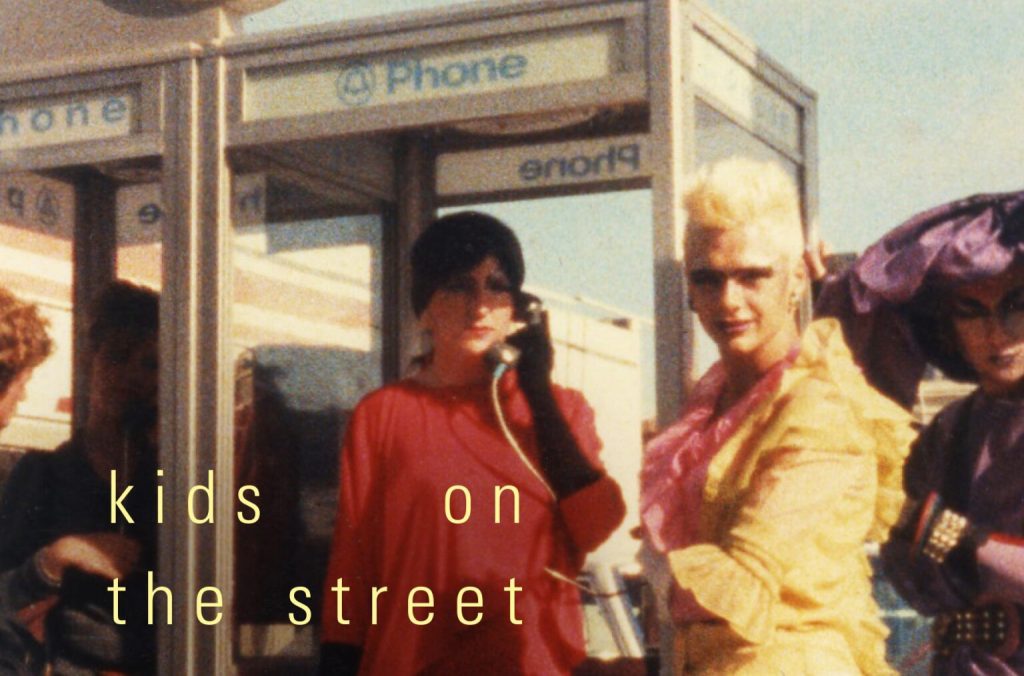

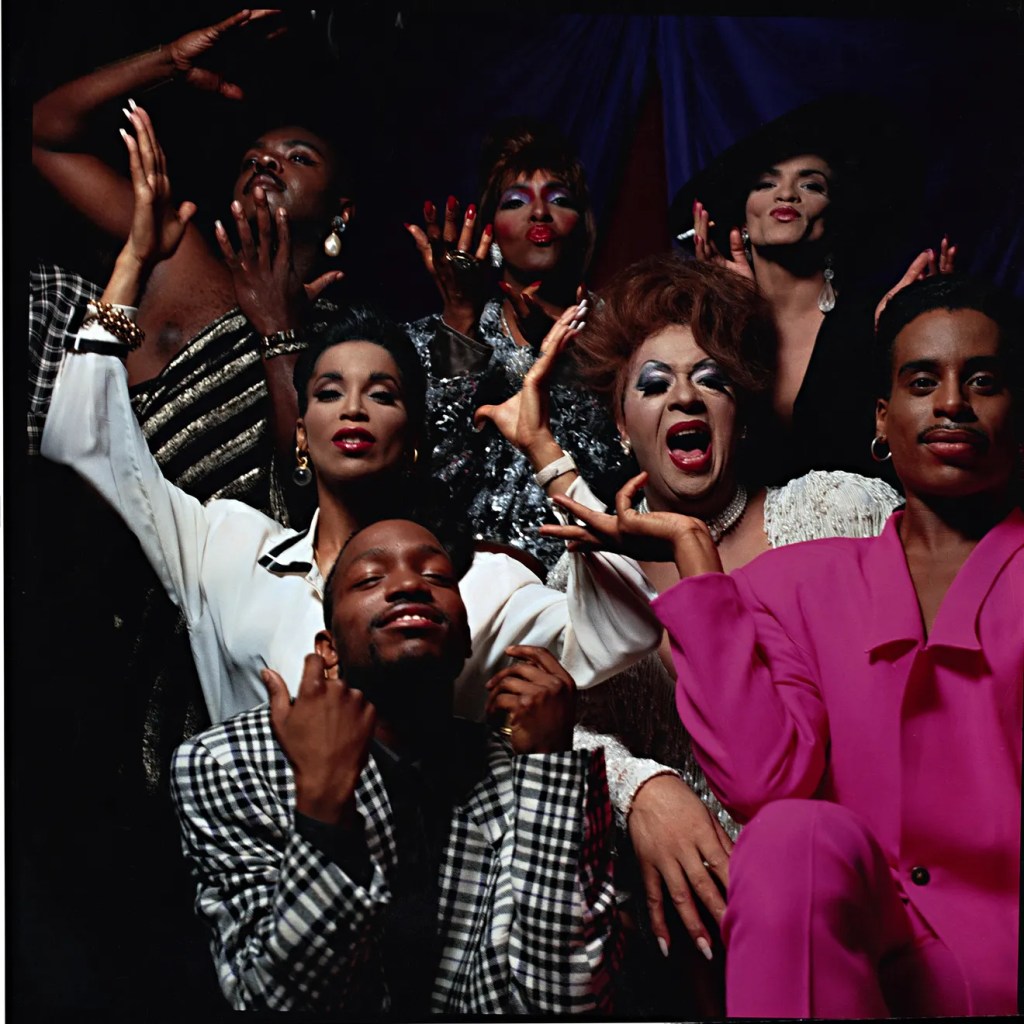

I remember often watching young gay men hustling tricks on Polk Street (San Francisco). When their parents kicked them out of their family home, many young men ran away to San Francisco and avoided homelessness (with varying degrees of success) by prostituting themselves to older men. Most of these hustlers lived across the street from the hustler bars in the Leland Hotel. To this day, queer and trans kids especially, face this same fate. (The most powerful documentation of this world was captured in Paris Is Burning in 1990.) In recent years homelessness has become a threat to a larger number of both young and elderly queers folks.

Privilege, whether, social, cultural, or economic, is a site of intersectionality. Because of my academic education I possess a great deal of cultural capital. As a working-class academic, I founded myself educated out of my working-class roots. I have a better grasp of how much bigger the world outside the blue-collar world is. I also face a lot of anti-intellectual prejudice. (Instead of congratulating me on earning a PhD, my mother informed me rather coldly that she would never call me “Doctor.”) Having been exposed to and moving in upper middle and upper-class circles I learned how my lack of money (multigenerational, career-producing salary, or understanding how money works through investment, speculation on the stock market) limited me. Having done all the right things, having ”played the game” of social mobility, I found myself poorer in adulthood than my parents had been.

When people pointed out that I have “white privilege”, I scoffed at the idea and pointed out my life’s trajectory. Gradually I came to understand that “white privilege” was not so much about what I had (or, in my case, didn’t get) than how many barriers our society places to block people of color from even getting in the door to social mobility. My shorthand for all of this is, of how I had not attained the economic success guaranteed me as a white person, is what I mean by “living like a white person.”

Only two weeks ago Donald Trump unleashed his Reign of Terror. All his white working-class MAGA supporters are about to find out Trump has never been interested in opening the door to social mobility to them. In fact, all the rights and relative privilege the MAGA folks perceive and hate people of color for having (at their expense) are about to be taken away from them too. They are about to learn that Trump’s victory is not their victory, they are not “one of ‘us’.” They will be living less than “like a white person” than ever before.

“Ain’t it hard”? Well, no, not really, at least not for me, not any more.