“We’re creatures of the underworld. We can’t afford to love.”

— Harold Zidler (Moulin Rouge)

“The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

–Oscar Wilde

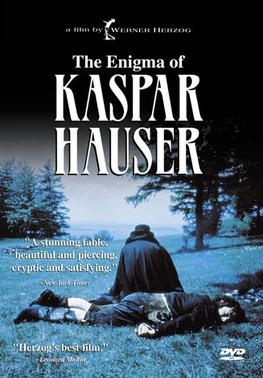

used to teach a literature course to college juniors I called “Foucault for Beginners and Others.” In keeping with academic jargon popular at the time, I described it as readings in “subaltern voices.” The term “subaltern” consists of two Latin words, meaning “below all others.” Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci coined the term as a codeword for any class of marginalized or oppressed people subject to the hegemony of another more powerful class. Postcolonial Studies scholars in India, including the best known Gayatri Spivak, examined the formation of subaltern classes in a variety of settings. The goal of subaltern studies is to provide a kind of counter-history to address the imbalances of “official” dominant culture histories. Because subalterns cannot speak directly for themselves they and their allies have used literature a means to give voice to their reality. In my Foucault course we examined texts where the subalterns speak for themselves, including One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Antigone, ZAMI: A New Spelling of My Name, and The Mystery of Kasper Hauser.

My hope in teaching this course was that my students would understand and develop empathy for those stigmatized and marginalized I hoped they would be able to understand how this dynamic works through the lens of Foucault’s “power/knowledge,” that is, “all knowledge is possible and takes place only within a vast network or system of power relationships that allow that knowledge to come to be, in order for statements accepted as “true” in any context to be uttered, and in order for what counts as knowledge to be generated in the first place” (Zachary Fruhling). I even hoped such insight might inspire one or more of them to become advocates for social justice. In the middle of one of my classes 9/11 took place. The next day all our Turkish and Saudi students had left the United States and were headed back to their home country. Some of my students were demonizing Middle Easterners.

When I was writing my memoir Resilience certain subjects emerged that I wanted to explore in greater depth. Since they were digressions outside the focus of my book, I set them aside to explore at length at a later time. One of those subjects arose from my intuition that there were important dynamics that connected my sense of isolation and loneliness growing up with the secret of my homosexuality, my sense of low self-worth, my isolation of the sexual aesthetic of hypermasculinity, the longing for community with other man like me, the sense of what Andrew Holleran called “doomed queens,” and my hunch that I shared these experiences as a gay man with other gay men of my generation. As I had done with my Foucault course I turned to literature, looking for other gay men, whose life experiences I identified with and to understand how those experiences had shaped us. Film and literature both reflect and create reality.

John Schlesinger’s film Midnight Cowboy spoke directly to my life experiences and my soul in ways I could not articulate. Annie Proulx’s short story Brokeback Mountain laid bare the tragedy of the apparent impossibility of gay love for people like me of my generation. As a teenager in the 1960s my best friend and I were also secretly lovers. Had college not been our escape from our rural lives (we went to schools at the opposite ends of the state), Brokeback Mountain could very well have been the story of our lives. I was introduced to Thomas Savage’s novel The Power of the Dog in the film version, released in 2021. Here I encountered a complex and subtle interweaving of social and psychological aspects of this gay loneliness. Setting his tale in 1925 Savage explores how repressed homosexuality manifested as homophobia in the masculine ranch world several generations before Stonewall. Landscape is an important character in Savage’s novel. Savage portrays something lonely and terrible of the West, embodying the emotional price you pay for being different.

*****

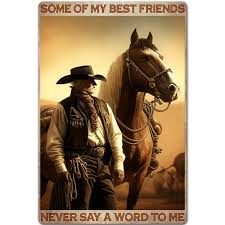

Common to all three stories is the mythic Cowboy. The cowboy has long been an icon of masculinity for many gay men, either as the object of sexual desire or as a model for how to “perform” their masculinity, presenting themselves as traditionally masculine. They typically also desire partners who also present in a traditionally masculine manner. For such gay men the American masculinity of the Cowboy is often “just right,” neither the performative homomasculinity of the leatherman or the performative effeminacy and conscious campiness of queens.

Mainstream society long held the belief that all homosexual men limp-wristed, lisped, were highly emotional, could easily to become hysterical, were vain, had a heightened fashion sense, made ideal interior decorators, were obsessed with colors, were sharp-tongued, and were interested in culture and the high arts. The rules of hegemonic (traditional) masculinity define gay men as ipso facto “feminine.” Performatively masculine, literally “straight-acting,” gay men could not escape this ontological prison. Homophobia is the policing agency that compels straight men to guard against showing any signs of femininity. Historically it has also engendered in many gay men a paranoia and a hypervigilance in which they police themselves for any signs of femininity.

Contrary to the “official truth” of governmental, academic, cultural, corporate, or scientific institutions, and contrary to gay folk wisdom, there have always also been gay men comfortable and secure in their masculinity. Jack Fritscher coined the term “homomasculinity” to distinguish the gay appropriation of the trappings of traditional heterosexual masculinity for its sexual desirability from the heterosexual men trying to live up to the masculine ideal. They have often found themselves crisis-prone, trapped in psychological contradiction, prone to depression, substance abuse, sexual assault, and domestic violence. The resultant (unrecognized) psychological trauma manifested in bullying and aggression was long normalized as the behavior of “real men.”

By the nineteenth century homoerotic practices (ranging from sexual acts to romantic attachment) became markers of a homosexual identity. Social control of such sexual behavior by the threat or imposition of indefinite incarceration or the death penalty broadened significantly. Homosexuals were not just sinners doomed to Hell and criminals requiring imprisonment, but also mentally ill. Homosexuals internalized all of this, which resulted in self-loathing and policing one’s own desires.

Foucault asserted that the complex web of beliefs generally accepted as “truth” or as “knowledge” by recognized authorities makes it impossible to “separate the vast web of power relationships from the vast web of beliefs, each of which feeds off the other in a relationship that is deeper than mere symbiosis or reciprocity.” What Foucault calls “power/knowledge” is “a single, vast web of power relationships and systems of knowledge, the majority of which are implicit and not commonly called attention to within any particular society, context, or institution, how that which has traditionally been considered as absolute, universal and true in fact is historically contingent” (Zachary Fruhling).

*****

The mythic cowboy began as a literary trope. In the nineteenth century Americans embraced the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, that the United States was destined to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific Coast. The Louisiana Purchase, the Oregon Territory, and the effort to re-annex Texas all provided the United States with the land to settle. Frontiersmen had explored these western lands and were soon followed by (mostly white) pioneers. Easterner settlers took ownership of the lands which the U.S. government’s policy of removing and exterminating Native Americans had prepared for settlement. The rise of the railroad accelerated the rapid westward expansion. The Wild West was tamed by Easterners bringing their “civilized” culture—their laws, their capitalism, their women—creating towns, ranches, marrying the women, and settling down in families.

The term “Manifest Destiny” was coined in 1845 to criticize opponents to the re-annexation of Texas. Disguising religious, political, and economic motivations, Manifest Destiny justified subduing the “wild west.” And it allowed Americans to pursue the “American Dream,” a term coined in 1933. In this fantasy land everyone would lead a richer, fuller, better life, based on opportunity limited only by one’s own ability. In this vision the “self-made man” could achieve anything he set his mind to.

The cowboy has been romanticized for some 150 years. This romantic version of the cowboy has been a symbol of a specifically American hegemonic (“traditional”) masculinity. First published in the years following the Civil War, fictional cowboy tales appeared in dime novels and quickly grew in popularity, spawning a rise in literacy.

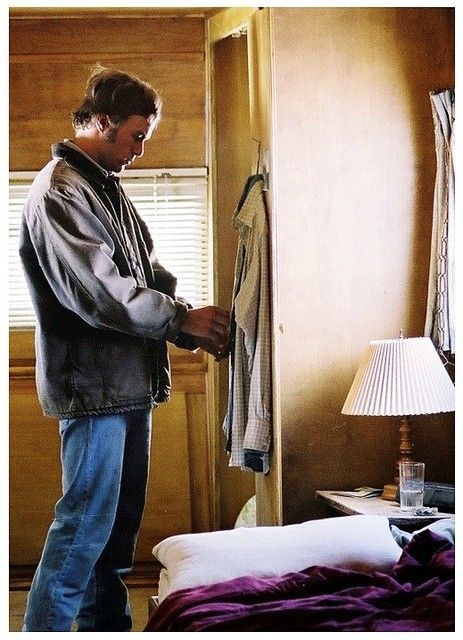

This mythic cowboy embodies both negative and positive qualities. He is rugged, strong, self-reliant, modest, confident, plainspoken, casual, independent, instinctual, and highly ethical. He typically wears bluer jeans, cowhide chaps, a denim or chambray cowboy shirt, a Stetson hat (in the movies, white for the good guy and black for the bad guy), western boot (ranchers usually wore rope boot), a colorful bandana (to keep the dust out of their face; they also come in handy when a cowboy turns bad and wants to disguise his identify), and a pair of six-shooters.

There were several historical cowboy cultures that preceded the American cowboy archetype. Elements of those cultures formed its foundation. America’s first cowboys were enslaved ancestors of the Gullah Geechee people in the Carolinas. Cow pens, cattle drives, and open range herding were important features in the agricultural landscape during the Colonial period in South Carolina. The word cowboys was originally “cow boys” because the enslaved Africans who took care of the cattle were usually male children — cow boys.

The first vaqueros in Mexico and in most of the Americas in the 16th century were mostly mulattos and blacks. They were horse-mounted livestock herders of a tradition that has its roots in Spain and was extensively developed in Mexico. The vaquero became the foundation for the North American cowboy. Its heritage remains in the culture of the Californio (California), Neomexicano (New Mexico), and Tejano (Texas).

In the United States the vaquero heritage had an influence on cowboy traditions which arose particularly throughout California (“buckaroos “), Hawaii, Montana, Texas, and New Mexico, each distinguished by their own local culture, geography and historical patterns of settlement, such as Hispanic and indigenous groups, ranching styles of eastern states, and traditions of western horsemanship.

All these historical precedents were condensed into the mythic American cowboy. He is an excellent horse rider, handy with the lasso and a gun. He works outdoors on a cattle ranch or on the trail herding cattle. He lives in an all-male culture, often on the trail with other cowboys, and sleeps in the bunkhouse with other cowboys when back at the ranch. He is often on his own, alone for long stretches of time, showing fortitude in solitude and sometimes pining for human companionship. This archetypal cowboy continues to be celebrated in novels, movies, television shows, and commercial advertising.

Actual cowboys, as George Derenburger has reported, did not engage in the fast draw, did not wear their revolver low slung, did not shoot from the hip, or fan a pistol, and wore chaps only when herding cattle. Stage coaches rarely carried a strong box full of gold. The Winchester rifle, not the Colt revolver, “won the west.” A medium allegedly told Sarah Winchester, the widowed daughter-in-law of the inventor of the Winchester rifle, that the ghosts of those killed by the rifle would haunt her for the rest of her life unless she moved out west and built a house with room for all of them. She spent the rest of her life adding rooms to the house and the eccentric Winchester House in San Jose, California remains a tourist attraction.

The first Hollywood cowboy was “Bronco Billy” Anderson in the silent film era. A steady succession of cowboy actors followed—Tom Mix, Gary Cooper, Randolph Scott, Robert Mitchem, Henry Ford, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, Wil Rogers, Gene Autry, and John Wayne, marking the classic era of the Western genre. In the postwar years Hopalong Cassidy and The Lone Ranger were staples of television aimed at children viewers. Gunsmoke and the Cartwright dynasty of Bonanza mirrored the American middle class of the 1960s. The Cartwrights were notably an all-male family, a widowed father and three unmarried sons all living together.

Little Big Man, first (?) Hollywood film to tell story from Native American point of view.

Black Robe (1991) Catholic missionaries in colonial Canada brutal attempt to convert native Americans, told from native’s perspective.

In real life Will Rodgers had been an actual cowboy, noted as a roper, who became a stage and film star as “America’s cowboy.” Deemed a cowboy philosopher, due to his homespun humor and commentary on American life, he gave voice to a sentimental version of the common man in the 1920s, which continued to find expression in the cowboy archetype. Common folks identified with his line, “All I know is what I read in the papers.” Gene Autry was known as the “singing cowboy,” an appeared on the radio, in films, and on television for three decades. Roy Rodgers, considered the greatest singing cowboy, had a children’s television show in the 1950s. John Wayne (whose real name was Maron Robert Morrison) succeeded Gene Autry as the iconic Hollywood cowboy.

This romanticized cowboy took a nuanced turn when the Hays Code was abolished in 1968. Native Americans began to be cast as protagonists. Strong women characterized emerged. Good guy –versus—bad guy plots were replaced with man—versus—nature plot devices. Psychological westerns appeared, recognized by their complex characters and multiple lot devices. These began with Shane and High Noon. Sergio Leone’s “spaghetti westerns” of the 1960s gave Clint Eastwood his acting start, playing the anti-hero gunslinger. Leone did not fully grasp and employ all the American values embedded in the western and used his films to explore European leftist politics of the 1960s.

In recent years such depictions of traditional masculinity have fallen into disrepute. Men were supposed to be tough, self-reliant, emotionally repressed, defenders of home and family, and upholders of the social order. These values are now understood as the cause of “toxic masculinity.” They produce acts of misogyny, homophobia, and violent domination. Exalted by the currently reigning radical right in the United States, its posterchild is Donald Trump.

He is misogynistic. He mocks women who do not bow to his view that women are meant to be subservient to men. He is a racist. Ho mocks the disabled, casts xenophobic aspersions on everyone not like him, and has ceaselessly and openly threatened retribution and implicit violence to anyone who is disloyal to him or defines him in any way. Trump appears to be incapable of showing affection, and with his presumable. inability to access his own emotions, only expresses anger, rage, and hatred. His thirst to be a dictator, the “ultimate” strong man who bends everyone to his will. He achieved goal with the blessing of the American people on November 5, 2024. Had this not happened, Trump would have to see himself as a “loser.” To be soft, weak, in short—feminine—is the ultimate insult and indignity for any “real man” in traditional American heteronormative society. In the newly born fascist United States during Trump’s current Reign of Terror the “toxic masculinity” of dictators will prevail.

There is an equivalent “queer toxic masculinity” in the gay community, based on cisgender white gay men “stigmatizing and subjugating femmes, queer men of color, and trans men via body norms, racism, and transphobia.” Attractiveness among butch men is based on appearing “straight-acting,” having a muscular body, a low voice, perhaps sorting a beard. While such intra-queer community stigmatizing may serve a useful corrective to bad behavior, it also typically conflates the negative judgment of misunderstood homomasculinity. Several cisgender gay men in the neofascist radical right ride the wave of classic fascist hypermasculinity.

The fact remains that no one has conscious control over who or what they find sexually attractive. And “queer masculinities” are every bit “performed” as the “natural” homomasculinity being condemned.

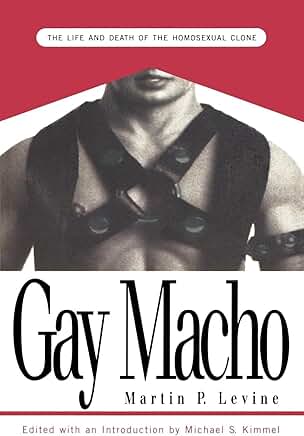

It should be noted that Phillip Morris and its “Marlboro man” ad campaign from 1954 to 1999 promoting Marlboro cigarettes. The commercials featured a handsome cowboy—usually framed alone in a beautiful western landscape, smoking a Marlboro, a “real man’s cigarette.” Some of the actors had been actual cowboys (and often of a conservative political bent). Noble from a historical sexual-political perspective was the only gay actor Christian Haren, who appeared in the ads in the early 1960s. When he was diagnosed with AIDS in 1985 he became an AIDS activist. (I knew Christian as a fellow neighbor in the Castro when he became an AIDS activist. I found him to be a gentle, humble, compassionate man.) The cowboy masculinity of the Marlboro cigarette campaign rendered the logo on the cigarette packaging itself a code for gay men, e.g. the Chicago gay bathhouse Man’s Country and the book cover design on Gay Macho: The Life and Death of the Homosexual Clone.

*****

The Jungian shadow, or shadow archetype, is an unconscious aspect of the personality that does not correspond with the ego ideal (how a person sees themself, what they believe themself to be). The shadow is “the self’s emotional blind spot.” The shadow personifies everything that the person refuses to acknowledge about themself. When an individual tries to see their shadow, they become aware of (and often ashamed of) those qualities and impulses they deny in themself but cab plainly see in others. In American society homophobia is the source of the homosexual shadow, the historically rooted clash within the gay man between his self-understanding as a man and society’s judgment that he can bever be a “real”: man, regardless of how well he “performs” his masculinity. Carolyn Kaufman noted that “in spite of its function as a reservoir for human darkness—or perhaps because of this—the shadow is the seat of creativity.”

Goffman’s book Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (1963) examines how, to protect their identities when they depart from approved standards of behavior or appearance, people manage impressions of themselves, mainly through concealment. He suggests that the experience of stigma differs based on the concealability of the stigmatized attribute. The discredited are individuals who have a stigma that is predominantly visible such as race/ethnicity, gender, or physical disability. Goffman relies extensively on autobiographies and case studies to analyze stigmatized persons’ feelings about themselves and their relationships to “normal” people. He looks at the variety of strategies that stigmatized individuals use to deal with the rejection of others and the complex images of themselves that they project to others. Goffman identifies one response of the stigmatized individual as hiding. Hiding can lead to further isolation, depression, and anxiety and when they do go out in public, they can, in turn, feel more self-conscious and afraid to display anger or other negative emotions. Gay men who choose to stay in the closet seek to avoid being discredited, to not allow our moral failings to be known. . The result of stigmatizing them (us) is to marginalize us and “spoil” our identity—stigmatizing us for our sexual behavior becomes the source that spoils our entire identity. It doesn’t matter if you are a brilliant scientist, a philanthropist, a married man who has fathered children, etc. All of that is invalidated and dismissed as irrelevant.

Kids who grew up feeling lonely may become adults who seek love where it’s not available, Isolate themselves when things go wrong, are always there for others but feel invisible, blame themselves when people hurt them, feel deep emptiness and loneliness inside and are known by many but still feel they have no real friends or deep connections. This results in a specifically gay loneliness that is profoundly bleak. They desire romantic relationships that cannot be.

*****

Sometimes loneliness is the price you pay for being different. The isolation that comes from feeling different is a cause of profound sadness. Lonesomeness describes the sadness that arises from the lack of companionship or separation from others. Loneliness is the sadness that arises from having no friends or company. Children who grow up feeling lonely often become adults who seek love where it is not available, isolate themselves when things go wrong, are there for others but feel invisible, blame themselves when others hurt them, feel deep emptiness and loneliness inside, and feel they have no real friends or deep connections with other people.

Hans Christian Andersen was the first to portray this archetype in his 1843 fairy tale “The Ugly Duckling.” This is the story of a duckling who is hatched into a world where the other animals perceive him as ugly. They abuse him verbally and physically. Terrible hardships ensue. After spending a miserable winter alone, during which the duckling grows into adulthood, he deicides that he can no longer endure his life of loneliness and hardship. He decides to end his life by throwing himself into a flock of swans, preferring to be killed by such beautiful creatures than to continue living as an outcast. To his surprise, the swans embrace him. Upon seeing his reflection in the water, he realizes he, too, is a beautiful swan and happily joins his true family. This fairy tale was of little comfort to young boys who grew up to be gay. Prior to the Stonewall uprising in 1969, many, if not most, of us believing we were the only one like “that,” there was no ugly duckling “happy rending” narrative for us.

Gay men are born “different.” We know we are different before we understand what makes us different. We are wounded by the homophobia of straight people who fear our difference. The wounding in childhood and adolescence increases the sense of being different. This sense of difference wounds us and we suffer from that wounding. “Suffering,” as Douglas Thomas has noted, is “an essential agent of paradoxical pleasure and psychological transformation.” At the core of the gay male archetype is the dynamic of “wounding difference.” That wounding also opens the door to inner exploration—for those of us who choose to explore. The three stories, both the original literary text and the film they were based on, that follow are “profoundly bleak” because each of them is a “a love story between men that cannot be.” Many trauma survivors see themselves as likeable but not lovable. Likeable, not lovable. Needed, but not wanted. Present, but not included. Observed, but not seen.

In 2013 literary scholar Julia Prewitt Brown identified Midnight Cowboy as a Bildungsfilm. The Bildungsroman has a long pedigree, notable among them Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship Years (Goethe) and Candide (Voltaire). These coming of age novels trace the moral and psychological growth of the naïve protagonist from childhood to adulthood. In his 1966 book review Paul Levine describes James Leo Herlihy’s Joe Buck as “the tragic implications of the death of a mythic hero and his rebirth as a man.” Herlihy grew up in the Great Depression in a working-class family in small-town Ohio and in Detroit. He knew from an early age he was attracted to boys but kept his homosexuality a secret. This left him profoundly isolated. (In 1993 Herlihy committed suicide in Los Angeles. He was 66.) He cultivated his writing craft at Black Mountain College, a free-wheeling, experimental, bohemian learning community. As a writer he wanted “to write a book about how cruel we are to one another, a book that tells that in such a way that the whole world will cry.” He drew inspiration from Upton Sinclair’s muckraking novel The Jungle. What most informs Herlihy’s prose writing was his mentor Anais Nin’s message, “If you want to affect the world, first of all you have to affect yourself.”

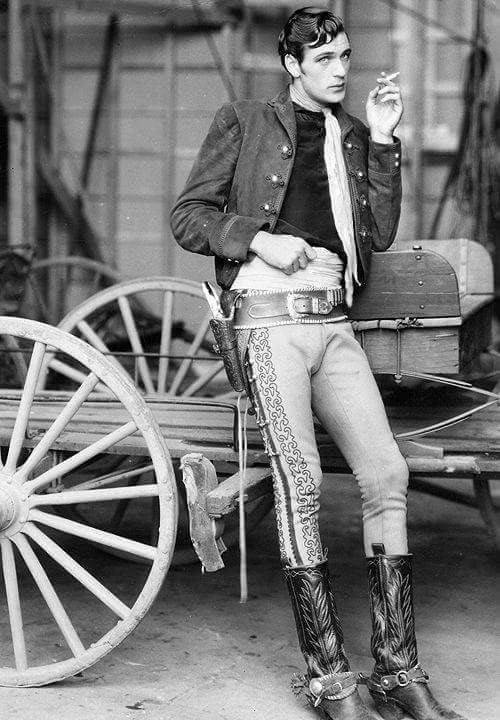

In 1969 gay Jewish director John Schlesinger released his film version of Midnight Cowboy. The basic plot of both novel and film cover the same territory. However, Schlesinger changes some small, but significant details. In both versions Joe Buck journeys from Texas to New York City to pursue his “American Dream” of becoming a prostitute servicing rich woman. He believes that New York women are starved for sex because the city is filled with “faggots.” His cowboy garb enhances his virility in his own eyes and believes it will draw women to himself like a magnet. Once in Manhattan, he fails miserably trying to hustle rich women and plummets ever deeper into poverty. In his naïve self-belief, once in Manhattan he discovers that he has taken on the coded garb of the male hustlers on Times Square. He sometimes sells himself there to men to survive the mean streets of New York.

Both novel and film follow Joe Buck’s journey from Texas to Times Square. In both Joe Buck’s upbringing by an indifferent grandmother, who was busy boozing and moving from man to man, Herlihy presents Joe’s life in chronological order, while Schlesinger uses flashbacks stressing attention to how this traumatized Joe in childhood. Herlihy both shows and tells how this caused Joe to grow up profoundly isolated and lonely, desperate for but unable to form connections with other people. Joe has brief dalliances with bath men and women, hoping to secure their friendship. Joe’s sexual desirability and availability to have sex is the only means he believes he has to find connection, approval, and acceptance. In the novel Joe attracts the attention of Perry, a male hustler in Houston, who misinterprets Joe’s interest as a mutual sexual attraction. Perry gets Joe high and Joe reacts by babbling tearfully about his heterosexual desires. To take revenge Perry takes Joe to a brothel where Joe has sex with a prostitute. He discovers he has been set up and is being spied upon. Joe ends up being raped by the madam’s son. Deeply traumatized by the rape and Perry’s betrayal, he decides to channel his anger and reinvent himself as a hustling cowboy in New York City. (This detail is left out of the film.)

Both Herlihy and Schlesinger probe the depths of the mythic Midnight Cowboy. Depths of Joe Buck’s alienation. Schlesinger’s film is a significant documentation of 1960s sleazy Times Square, the underbelly of Manhattan—what John Rechy described as “the magnet for all the lonesome exiles jammed into this city.” It vividly captures the Manhattan of 1969, which sparked the Stonewall riots. Midnight Cowboy was released in the same year as Stonewall.

Two other snapshots of 1960s gay Manhattan to consider: The film version of Matt Crowley’sThe Boys in the Band, set in 1968, was released in 1970. It portrays a circle of gay men in the 1960s gathered for a birthday party for one of the friends. The film stands as a document of another class of New York gay men. All the characters are bitchy and self-loathing. In a nod to Midnight Cowboy Crowley renamed the male prostitute bought as a birthday present “Cowboy.”

Joe Buck’s journey proceeds with his arrival in Manhattan, including his exchange with the woman who answered his come-on question—“Where is the Statue of Liberty?—with the flippant “It’s up in Central Park taking a leak,” an incident he vividly recalls from his own arrival. He picks up a woman who takes him to her apartment and becomes enraged when he asks her for money. Buck ends up giving her money, which he is quickly running out of. He meets Ratso, a crippled con artist, who Buck immediately seizes upon, like a drowning seizing a life buoy, as his first friend and who offers Buck to be his “manager.” In the novel, Ratso is young and blond. In the film he is dark-haired and vaguely older. In the novel Joe is dark-haired, his hairiness underscoring his masculinity.

Ratso sets Joe up with a religious fanatic, who Joe flees from.

He picks up a teenage boy in a movie theater who gives him a blow job. The teenager throw up. It turns out he has no money. In the book the scene takes place on a rooftop, but in the film in the movie theater’s men’s room.

Joe runs into Ratso again and Ratso invites Joe to move in with him in an abandoned building. Ratso describes his vision of living to Florida. They are invited by Hansel and Gretel MacAlbertson to a weirdo party,” based on the parties at Andy Warhol’s Factory. Joe tries to have sex with a woman but find himself impotent. Herlihy makes clear that this is to connect Joe’s gayness. Schlesinger’s version only hints at this, making Joe’s anxiety at the party the direct cause.

He and Ratso are thrown out of the party. Ratso falls down a flight of stairs, the plot turn that puts the two on the road to Florida. As Ratso get sicker and becomes immobilized, Joe promises to take care of both of them. The vision of what awaits them in Florida rapidly reveals itself as the fantasy that it is, as the hopes that have been keeping them both going on. In both version Ratso dies on the bus. In the novel, Joe returns to the bus to find Ratso dead. Joe now takes on the responsibility for him and vows to find a regular job so he can make money to pau for Ratso’s funeral and headstone. He points his arm around his dead friend, embracing him as the friend and companion he had always sought. In the film Ratso pisses his pants and starts crying because he has lost control. In the film he clearly idealizes and loves Joe, despite his endless homophobic remarks, It is clear that Ratso represents Joe Buck’s own crippled self, his shadow self. As Herliny wrote, “the day Joe lost his innocence was when he awakened to his own lonesomeness.”

As best as I can recall, Charles Kaiser reported in The Gay Metropolis an upper-middle-class gay man who described the gay life he knew in New York at that time as “quite comfortable.”

James Leo Herlihy grew up in the heart of the Depression, first in Detroit, then Chillicothe, OH. When his dad injured his leg and could no longer work, the family sank deeper into poverty. At the Catholic school his parents sent him to “nine of the ten nuns that I studied under were insane.” Already at an early age he knew he was attracted to boys, and knew he had to hide his feelings. This left him feeling isolated and gave him a sense of how grotesque and lonely the world could be.

Herlihy modeled Midnight Cowboy on The Jungle. Herlihy wanted “to write a book about how cruel we are to one another, a book that tells that in such a way that the whole world will cry.” He “wanted to do something for the world …[but also]… to understand what it meant to be a fulfilled individual.” As Anais Nin, told him, “If you want to affect the world, first you have to affect ourselves.” Being a writer meant to him that he could be thew observer, the outsider, engaged yet protected. God’s lonely man. For a while he studied at Black Mountain College, a very experimental and bohemian learning lab. His was his entry into the bohemian life of postwar America, where he befriended Anais Nin and other writers. He moved to LA and then in 1952 to NYC, which had the world’s largest gay population. Here he was introduced to Christopher Isherwood. Of his years in NYC, he wrote he made “no intimate friends. I’m not lonesome, I am lonely.” Herlihy met and became romantically involved with Dick Duane. Through Duane, Herlihy had “one foot in their world (i.e., his own working-class family) and the other in New York. Not surprisingly, he often felt like he didn’t belong in either world.

In 1984, George Orwell’s exploration of how fascist systems control entire populations by obliterating any sense of individuality, he wrote “The Most Terrible Loneliness is not the kind that comes from being alone, but the kind that comes from being misunderstood, it is the loneliness of standing in a crowded room, surrounded by people who do not see you, who don’t hear you, who do not know the true essence of who you are. And in that loneliness, you feel as though you are a ghost, a shadow of your former self.” This is exactly how homophobia functions, separating the homosexual individual from society as well as alienating him from himself.

In The Power of the Dog Thomas Savage contrasts how two different men cope with their homosexuality. Phil comes from a wealthy Montana rancher family and is a Yale-educated scholar. In his youth he had fallen in love with a rough-and-tumble cowboy. Phil is an asshole—his homophobic attacks are projection and deflection acts of self-preservation. He is trapped by his masculinity, and remains lonely.

What Phil Burbank (played by Benedict Cumberbatch in the film version) knows about himself is terribly unspeakable. He has remade himself as a manly, homophobic rancher. Phil turns his repressed homosexuality into homophobia in masculine ranch world. Behind this is his own internalized homophobia, creating profound loneliness in him.

Peter Gordon (played by Kodi Smit-McPhee) is the sissy son of the innkeeper Rose Gordon (played by Kirsten Dunst). Rose represents the sex Phil doesn’t desire, but a person he doesn’t have under his control. He is home on a break from college back East. He is fond of making paper flowers. Peter has a secret, too. He has stumbled across Phil bathing naked at a secret watering hole and masturbating with a delicate scarf that once belonged to Bronco Henry (“the ideal cowboy of Phil’s youth”). Peter also discovers a stash of Bronco’s homoerotic magazines. Phil notices Peter and chases him away. (It should be noted that they are both celibate gay men.) Phil has desired, touched, and loved his hero, Bronco. Bronco had died a horrible death which took place in front of 20-year-old Phil’s eyes.

Eventually Phil is taken by Peter’s confidence and curiosity. It becomes clear that Phil is secretly attracted to Peter and had only felt this way before about his hero Bronco Henry. Later, in front of his men, his brother George and George’s wife Rose Phil makes amends with Peter, offering to plait him a lasso from rawhide before he returns to school. He teaches Peter to ride a horse. (George had revealed earlier that Phil was a brilliant Classics student at Yale, in contrast to his rough nature. The East may be read as feminized civilization and the West as a brute force that toughens and shapes “real” men.)

Phil had always mistrusted Rose, believing she was a gold digger who married George for his money. Phil also belittles her teenage son Peter, deriding him as weak and effeminate. He humiliates and upsets her during her piano performance, which leads to becoming an alcoholic. Upon learning about Phil’s policy of burning unwanted hides, Rose defiantly trades them to local Native Americans. Coming home from selling hides Rose falls sick and takes to her bed.

Upon discovering this, Phil is infuriated. Peter pacifies Phil by offering him strips from the hide he cut, not mentioning its origin. Phill gives Peter the rawhide rope he is braiding as an act of friendship. Phil is touched by Peter’s gesture and holds him close to his face. The pair spend the night in the barn finishing the rope. Blood flows from Phil’s open wound as he swirls the hide in the solution used to soften it. At this point he tells Peter about his hero Bronco. Peter asks Phil about his relationship with Bronco Henry. Phil says Bronco Henry had once saved his life when they were caught in a freezing storm in the mountains by keeping him warm with his body. Peter asks if they were naked, but Phil does not answer. They later share a cigarette.

The film is also about how a sociopathic young man (Peter) exploits the weaknesses of an emotionally damaged older man (Phil). Peter is motivated by the desire to free his other from Phil’s cruelty. Peter kills Phil, the man who has expressed affection for him, out of “homosexual panic.” As Phil is imprisoned by “toxic masculinity,” Peter is imprisoned by “toxic gay masculinity.” The only clear moral of Jane Campion’s film is that heterosexual family values by rendering the homosexual (Peter) a stereotypical homicidal monster.

To wit, Peter headed out on his own one day and found a dead cow. After carefully putting on rubber surgeon’s gloves he brought in his backpack, he cut off pieces of its hide. Phil and Peter ride into the hills together. While trying to catch a rabbit hiding in a pile of wood posts, Phil gashes his hand but declines Peter’s offer to dress the wound. Peter tells Phil about finding the body of his alcoholic father, who had hanged himself, and having the strength to cut him down.

The next morning, George finds Phil sick in bed, his wound now severely infected. A delirious Phil looks for Peter to give him the finished lasso, but George takes him to the doctor. Phil dies. Later, George picks out a coffin for Phil, while his body is prepared for burial. At the funeral, the doctor tells George that Phil most likely died of anthrax. This puzzles George, as Phil was always careful to avoid diseased cattle.

The Power of the Dog begins with a graphic depiction of bulls being castrated. The scene represents, both literally and figuratively, harsh and brutal facts of cowboy life, then “true grit”—the passion and persistence required-of Western masculinity. Castration is also the physical act of emasculation. This is arguably the greatest fear of a “real man.” It symbolizes homosexuality as feminized masculinity. Placed as the opening scene, it foreshadows the self-castration and sadism that will drive the motivation of its key characters, Phil and Peter.

By the film’s end, Phil has destroyed himself by handling the lasso he had made for Peter with his bare hands and getting a splinter and dying from the anthrax which infected the rawhide. While Phil had been trying to get close to Peter, seeking the connection and happiness he had had with his mentor and hero Bronco, Peter had been manipulating Phil’s vulnerability to protect his mother and kill Phil. The story ends on a final, revealing twist. Peter skipped Phil’s funeral and has gone home. He is in his room handling the rope that Phil had made for him with gloved hands. Peter pushes the rope under his bed and dismisses it, as he had dismissed Phil. Looking out the window he sees George and Rose come home and embrace. At this Peter smiles to himself. Phil’s masculinity, openly performed as a public display, has been conquered by Peter’s masculinity, performed as “inadequate,” yet triumphant in its covert execution. Nonetheless, Peter is now alone.

The novel’s title is taken from Psalm 22 in the Book of Common Prayer, read at funeral rites. During the funeral Peter is In his room reading Psalm 22:

Dogs surround me,

a pack of villains encircles me;

they pierce[e] my hands and my feet. (…)

Deliver me from the sword,

my precious life from the power of the dogs.

Rescue me from the mouth of the lions;

save me from the horns of the wild oxen.

The dog of the story’s title is an outcropping of rock, which Phil saw when he came to the area. Phil sees it as proof of his sharper and special sensitivity. The dog appears to be in pursuit of frightened prey. Phil asks Peter, “what do you supposed Bronco saw? Peter says, “the running dog.” Peter saw it when he first arrived there. This links Bronco, Phil and Peter in a chain of repressed homosexual love for each other. The power of the dog has made the relationship between these men impossible.

Despite the psychological complexities of the film and the fact that it turns on homosexual stereotypes—one a self-loathing asshole who dies at the end and the other a sociopathic (and mother-loving) monster—some straight reviewers and, notoriously, actor Sam Elliott, long a gay icon of cowboy masculinity, denounced the film as “shit.” This was in keeping with the reception of Brokeback Mountain, despite its cinematic brilliance, was snubbed by being passed over Hollywood Academy, for a best picture Oscar. In both cases heterosexual viewers refused to recognize gay men as “real, actual human being,” like themselves. This remains at the core of gay loneliness and unprocessed. Such is the source and the power of the dog.

*****

So far it has not been noted that the short story and the film were created in the background of an America gripped by the brutal murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay college student. In 1995, Shepard was abducted, beaten and raped during a high school trip to Morocco. This caused him to experience depression and panic attacks, according to his mother. Shepard was hospitalized several times due to his clinical depression and suicidal ideation. On the night of October 6, 1998, Shepard was approached by Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson at the Fireside Lounge in Laramie and offered a ride home. Instead, they drove to a remote rural area, where McKinney and Henderson robbed, pistol-whipped, and tortured Shepard, tying him to a split-rail fence, leaving him to die. He was taken by rescuers to a hospital in Fort Collins. Six days later he died from sever head injuries received during the attack. Proulx’s story was written in 1996 and published in 1997.

The play The Laramie Project was first staged in 2000. The dialog was composed of transcriptions of quotes by those connected with Shepard’s murder and the ensuing trial of his murderers. Both were given two life sentences each. The play has often been used as a method to teach about prejudice and tolerance in personal, social, and health education and citizenship in schools. The Matthew Shepard Foundation continues this educational work. Shepard may be remembered as a lesson in homophobia much as Anne Frank is remembered as a lesson in antisemitism. The true pain of vilified gay men is realizing we have no control over homophobes.

“Brokeback Mountain,” Annie Proulx’s 1997 short story and Lee Ang’s 2005 film based on the short story, imagines an impossible love story between two actual cowboys in pre-Stonewall American West. Set in 1963, the story is written from the perspective of mainstreamed gay men, which replaced the gay liberationist spirit following Stonewall. Midnight Cowboy was written by an out gay man and the film directed by another out gay man. The Power of the Dog was written by a gay man and the film was directed by a straight woman. Brokeback Mountain was written by a straight woman and the film made by a straight man. Ang Lee is the only non-American, having grown up in Taiwan. The profound shift in focus is from Midnight Cowboy and the Power of the Dog, the loneliness caused by unexamined internalized homophobia, to a study of the crippling effects of internalized homophobia as seen from heterosexual observers, holding heteronormative society accountable. The characters in the former works are so oblivious that they cannot even conceive of the potential for a homoerotic connection. In the latter work experience homoerotic intimacy but are unable to realize their desire for couplehood outside the privacy afforded by their isolated rural paradise. Even there they do not escape the damning eyes of heteronormative society. (The overseer spies on them with his binoculars, seeing them in flagrante delicto.)

Brokeback Mountain tells the story of two young cowboys, Ennis del Mar (Heath Ledge) and Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) who spend the summer of 1963 working high up in the mountains of Wyoming and form an intense emotional and sexual attachment. Over the next twenty years they continue to meet on Brokeback Mountain for brief liaisons on camping trips. They live separate heteronormative lives (marriage, children, and jobs), keeping their homosexuality and the true nature of their “fishing buddies” relationship secret. Jack Twist fantasizes a future of them living together on a ranch. Ennis Del Mar

is more emotionally conflicted and is tormented by his internalized homophobia. After one parting, Ennis steps into a doorway and wretches, torn between his love for Jack and his inability to accept it. In an emotionally charged scene, a tear-filled Ennis declares, “I wish I could quit you, Jack Twist.” This heartbreaking iconic scene captures how homophobia creates a “love that can never be.”

Once it becomes clear to Jack that Ennis will never be capable of a shared life together, Jack visits Mexico for gay sex, meets a very handsome, married, and closeted bear, and is eventually murdered and his body left in the desert. (When he was a child, Ennis’s father instilled in him the fear of being a queer by showing him the mutilated body of a gay cowboy, murdered and left by the roadside.) When Ennis learns of Jack’s death he visits Jack’s ex-wife and his parents. The coldness and contempt Ennis encountered makes clear they were all aware of the relationship. When Jack asks for Ennis’ ashes (to scatter on Brokeback Mountain), Ennis’s parents flat out refuse, but permit him to visit Ennis’s childhood bedroom. In this iconic scene Jack finds a postcard of Brokeback Mountain pinned to the closet door. He takes one of Ennis’s shirts out of the closet and buries his face in it, smelling Jack’s scent. Jack puts a shirt of his own over Ennis’s shirt on a hanger, symbolically uniting them forever.

Proulx’s short story is composed of an episodic series of memories Ennis has in his trailer after awakening from a dream. Proulx had written that “I watch for the historical skew between what people have hoped for and who they thought they were and what befell them.” While the story is told by an omniscient narrator, it all takes place in Ennis’ mind. Their relation is recounted from Ennis’ point of view, informed by his subjective perspective. In other words, the relationship is recalled by a broken hearted and grieving partner. Ennis remains conflicted by his internal homophobia and may still not understand either the cause played in preventing the relationship from of his internal conflict of emotions or the role he played in preventing the relationship to blossom. The short story is a masterpiece of brevity, portraying in rich detail the prison of loneliness heteronormative homophobia drives some gay men to masochistic self-enslavement.

Some gay viewers have decried the film as just another cliché of the homosexual being murdered, getting the comeuppance that satisfies the heterosexual audience. One gay film scholar pointed out that the film offers two readings—the homosexual as a tragic and flawed figure or the homosexual as a deviant predator. This scholar interprets Jack as a sexual predator, who by practicing his homosexuality (marking him as the “deviant”) recruits and corrupts Ennis, the masculine straight male. In this reading Jack is deemed “more homosexual” than Ennis. This scholar chastises the film for creating a “new level of homophobic discourse.” It is disappointing when a film, or any work of art, is dismissed for failing to be the story or vision the viewer wants it to be. At the time of their publication both Matt Crowley’s The Boys in the Band and Larry Kramer’s Faggots were scorned by many gay men for being gritty realistic representations of gay men instead of the flattering vision of how they wanted straight audiences to see us. It strikes me that such hostility is more about gay men’s shame.

Ang Lee’s film examines the homoerotic subjectivity more from a sociological perspective of an outsider. Ang Lee is a heterosexual man and originally from Taiwan affording him the perspective of a sympathetic observer. His aesthetic sensibility, in fact, transforms the love story of two poor cowboys into an archetypal tragedy. This is what Brokeback Mountain presents: Ennis and Jack never talked about the sex, they let it happen, at first only in the tent at night, then in the full daylight with the hot sun striking down, and at evening in the fire glow. Their sex is quick and rough, both men laughing and snorting. They don’t say a single word, except for the one time Ennis said, “I’m not no queer,” and Jack chimed in with “Me neither. A one shot thing. Nobody’s business but ours.” Their sexual union would prove to be their only brief respite from their individual loneliness.

I appreciate the film for deconstructing the traditional American masculinity of the “cowboy” ideology, revealing how homicidally destructive the normalizing ideologies of hypermasculinity, heteronormativity, and Christianity. (Gay sex was widely practiced in the Middle Ages, until Peter Damian decried homosexual sodomy in his 1049 Liber Gomorrhianus. He hoped to persuade the pope to depose church officials who practiced sodomy.) Employing cowboy tropes, iconic framing shots, and the backdrop of the vast emptiness of the American West, Lee creates a classic gay tragedy—internalized homophobia renders some gay men incapable of intimacy.