“Linking is particularly important in cultural history, because culture is a web of many strands; none is spun by itself, nor is any cut off at a fixed date like wars and regimes.” Jacques Barzun

Philosophers and historians give us visions of the world (William James) “There is nothing personal about facts, but there is about choosing and grouping them. It is by the patterning and the meanings ascribed that the vision is conveyed.” (Jacques Barzun)

1

I belong to the first TV generation. From my youngest years TV has entertained and educated me about the larger world. I was oblivious to how distorting the filter of televised reality was. I had no way of knowing. I didn’t know anyone who lived in a house as large as the one in My Three Sons. I didn’t know anyone as fatherly as Jim Anderson (Robert Young) in Father Knows Best or Ward Cleaver (Hugh Beaumont) in Leave It To Beaver. (Years later I learned through the gay grapevine that Tony Dow, who played the Beaver’s older brother Wally, was admired for his allegedly huge cock.) The Ricardos (I Love Lucy), the Kramdens (The Honeymooners), the Petries (The Dick Van Dyke Show) were not like anyone I knew.

When I was ten Dad moved our family from Syracuse, New York, a medium-sized city, where I was surrounded by a large extended family, to Preble, New York, a rural four corners into a house halfway between two dairy farms. Mom became friends with Ginny Griswold, a farmer’s wife at the other end of the valley. The Griswolds had five boys. I had a secret crush on the oldest boy, the very handsome Mark, who had bushy dark eyebrows and a football player’s build. The boys were all busy with farm work and had no time to play with me when Mom brought me with her on her visits. The sitcom Green Acres was popular at the time and I identified with Lisa Douglas (Eva Gabor), desperately wanting to move back to the city. I’d never been to Manhattan, but I knew I also belonged in a Park Avenue penthouse.

I loved Dobie Gillis, which included the beatnik character Maynard G. Krebs (played by a young Bob Denver). Krebs was a spoof of teenage rebels of the day, who imitated the lifestyle, if not the values, of the Beats—Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsburg, and William Burroughs—the iconoclasts of Eisenhower America. I was intrigued by Dobie’s beatnik sidekick. And I was curious about what beatniks were, where they came from, where they lived, and what they actually did. When I was seven I went to a Halloween costume party at our church where I saw a kid in a beatnik costume—black trousers, black turtleneck sweater, and black beret. I began discovering clues about these people who refused to conform to society’s values.

Later cultural scholars would identify Dobie Gillis as a symbol of the traditional and highly conformist values of Eisenhower’s 1950s America and Maynard G. Krebs as a harbinger of the counterculture of the 1960s. I was the “perfect little boy,” trying to please everyone, on the path to become another Dobie Gillis. I was taught to be polite to adults (as Mom often repeated, “Children are to be seen and not heard”), to behave in public, to not talk back to my parents, to work hard in school. From an early age I was a voracious reader. When an IQ test showed I was of above average intelligence—in fact, extremely smart–I was pushed to excel academically. And, unlike Dobie Gillis, I did.

I homed in on Maynard G. Krebs’ eccentricities. He played bongos (I took piano and cornet lessons). He collected tinfoil and petrified frogs; I collected stamps, postcards, and coins. He avoided authority figures and I would grow up to “have a problem” with authority figures and with following the rules. He loved jazz (something typical of the Beats) and detested Lawrence Welk. I detested Welk as well. And when I could I listened to rock-and-roll music, which Mom banned in our household. (She loathed “Elvis the Pelvis.”) Maynard avoided romance, serving as a foil to Dobie Gillis’s entanglements with girls. I loved Dobie’s first girlfriend Zelda (Sheila Kuehl), who disappeared after the first season. (Kuehl’s acting career ended when it became known she was a lesbian.) Meanwhile, I was reading Robert Heinlein’s juvenile novels, where girls and romance never appeared. I had no interest in girls. I had a secret life no one knew about. Tom Phillips–my best friend growing up in the country—and I were also secretly lovers.

Maynard G. Krebs introduced me to the possibilities of nonconformity. Beatniks awakened in me a longing for a world beyond Green Acres, planting a seed in my heart and mind for a world I would later learn was called Bohemia. This is how the Beats initiated my subversion.

2

The “real” bohemia is always somewhere in the past. This has been so since the idea of bohemianism first emerged. The term “Bohemia” (currently a part of the Czech Republic) first appeared in post-revolutionary France. At the time it was erroneously believed that gypsies (the Romany people) came from that region of Central Europe. In fact, scholars have traced Romany origins to India, most likely Rajasthan. A nomadic people who first left the Indian subcontinent around 1000 CE, they arrived in a Black Death-riddled Europe during the calamitous fourteenth century.

The term, as applied to modern society, arose after the French Revolution. This was a society where the old rigid social order had collapsed and modern industrial capitalism was growing. Traditionally, artists, composers, and writers had been supported by upper class patrons, and later by upper middle class patrons. Think of Michelangelo, who was commissioned by papal rulers to create his statues of the Pietà and David and to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Think of Bach, who was supported by the churches he composed music for. Think of Rembrandt von Rijn, who was commissioned by the wealthy merchants of Holland to paint their portraits. Think of child genius Mozart, who was supported by his aristocrat friends. Think of Voltaire, whose financial support came, first, from manipulating the patronage system in France and later, when he fell out of favor, was able to achieve financial independence by the pure luck of winning a substantial sum through a complicated government lottery system. That income was soon supplemented when he inherited his father’s fortune.

As it became possible for artists to support themselves by selling their art, they gained relative freedom to express themselves through their artistic pursuits. Artists in France began to identify themselves as “bohemians.” Bohemianism came to refer more broadly to the unconventional lifestyle of those involved in musical, artistic, spiritual, and especially literary activities. The umbrella concept extended to include a wide range of social outsiders, from criminals and vagabonds to flouters of the conventions of bourgeois respectability to political (Utopian socialist) and sexual nonconformists.

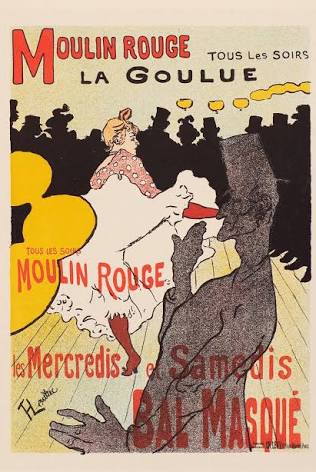

The bohemian lifestyle and aesthetic was first popularized by the French writer Henri Murger, who based his book Scènes de la vie do bohème

on his own life as a “desperately poor writer living in a Parisian garret.” The book became the basis for numerous retellings, from Puccini’s opera La bohème to Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge and Jonathan Larson’s Rent, set in the bohemian milieu of New York City during the AIDS epidemic.

3

Mom and Dad were born during the Great Depression and grew up during World War II. In those pre-television days Americans went to the movies every week. In the 1950s Mom continued this habit. She did not discriminate among the films she took me to see. There were often films about adult life I was too young to understand. Some were understandable enough for me internalize sexual taboos. The Troy Donahue vehicles A Summer Place and Parrish were real shockers.

One film that resonated deeply within me, for reasons I did not understand at the time, was Bell, Book, and Candle. I saw it when it was released in 1958. I was five years old. It depicts a fictional world of witches in 1950s Manhattan. The drama focuses on the lives of modern-day witches who must keep knowledge of their existence as witches a secret from normal humans. My growing awareness of my queer desires made it easy for me to identify with them as social outsiders. The conflict revolves around the perils of a witch falling in love with a normal human. If Gillian (Kim Novak) falls in love with Shep (James Stewart), a book publisher who lives in the building unaware that it is full of witches, she will lose her powers. Other characters include Novak’s bongo-playing warlock brother Nicky (Jack Lemmon) and two other witches, played by Hermione Gingold and Elsa Lanchester.

Without a conscious understanding, I picked up on Nicky’s eccentricities. His bongo playing was code for beatnik and his avoidance of romance subtly suggested underlying homosexuality. I was attracted to Aunt Queenie (Elsa Lanchester) and Bianca de Passe (Hermione Gingold). Like Rosalyn Russell’s Auntie Mame, their performances hold a camp appeal for gay male viewers. They all lived in Greenwich Village (never named in the film), long a home to bohemian types—creative folk, political radicals, eccentrics jestingly called “characters,” and homosexuals. Again, without conscious awareness, I found myself drawn to this tribe and the subculture they created.

A bookstore in the film that caters to the Greenwich Village crowd is named Bell, Book and Candle. Playwright John Van Druten suggests a connection between the modern-day witches and the medieval Roman Catholic Church. Traditionally associated with the strange or miraculous, these items were once used in an excommunication ritual for individuals who had committed an exceptionally grievous sin. Like Van Druten’s bohemian witches, queers in the 1950s ran the risk of being banished from society, should their true selves be discovered.

In the film, ironically, the witches fear losing their magic powers and being cast out from their outsider community. The film’s plot revolves around the budding romance between Gillian and Shep. If a witch falls in loves with a “muggle” (to borrow J. K. Rowling’s term), they will lose their powers and have to leave their world. Gillian falls in love and loses her powers. Her banishment from her world is underscored when her familiar, her cat Pyewacket, abandons her.

4

The first self-identifying bohemians in the United States—young, cultured journalists—gathered at Pfaff’s beer cellar in Greenwich Village in the years just before the Civil War. Notable among this group was Walt Whitman, the great American poet who celebrated American democracy and “athletic love.” (The word “homosexuality” had not yet been coined). He openly celebrated homosexual desire in his Calamus poems and he practiced it with joy.

No doubt, Whitman had sex with some of the other male patrons of Pfaff’s. His own preference for working-class men is well documented, as is his now notorious denial of being a “homosexual,” when the term reached American shores. The English advocate-practitioners of Whitmaneque athletic love included Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds, who both maintained a friendly correspondence with Whitman and shared his taste for working-class men, which they celebrated as “democratic love.” I am also turned on by working-class masculinity. And the subculture I came out into seemed “democratic,” where men of various ages, economic circumstances, and a broad range of body sizes and attractiveness mingled freely, both socially and sexually. Nowadays I am quite aware of the complex and often cruel hierarchies of sexual attraction, age, and material wealth in the gay world, as well as the freedom once granted to me based on my youth and attractiveness.

The American journalist and author Bret Harte first identified bohemia to the reading public as a place that “has never been located geographically, but any clear day when the sun is going down, if you mount Telegraph Hill, you shall see its pleasant valleys and cloud-capped hills glittering in the West.” [Theatre West: Image and Impact, 17-42] Mark Twain and Charles Warren Stoddard both considered themselves bohemians.

George Serling crystalized the term, writing “There are two elements, at least, that are essential to Bohemianism. The first is devotion or addiction to one or more of the Seven Arts; the other is poverty. Other factors suggest themselves: for instance, I like to think of my Bohemians as young, as radical in their outlook on art and life; an unconventional, and, though this is debatable, as dwellers in a city large enough to have the somewhat cruel atmosphere of all great cities.” [Garrets and Pretenders: Bohemian Life in America from Poe to Kerouac, 238]

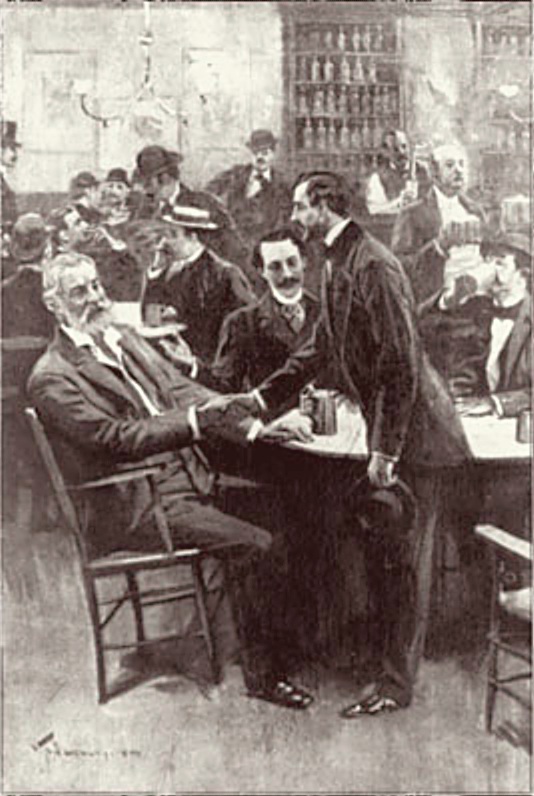

A group of self-proclaimed bohemian artists and journalists who gathered regularly in San Francisco, including Twain, Harte, and Serling, formed the Bohemian Club. (Jack London joined in 1904.) They gathered at the Bohemian Grove on the Russian River in California’s Sonoma County. It was a scene of heavy drinking (numerous members later became full-blown alcoholics). The Bohemian Grove is now a highly guarded, isolated compound, where world leaders gather informally and where major world decisions are often made based on private conversations among this elite.

5

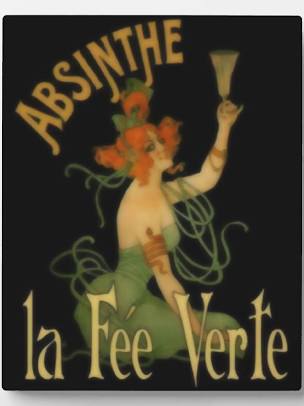

Bohemian artists accepted poverty as the price they paid for their freedom to create. Some embraced poverty as a lifelong condition. Others accepted it with the expectation they would one day become commercially successful, understanding that poverty was a temporary stage they had to pass through. (Moulin Rouge, for example, pivots on this hope.) Many writers, painters, and musicians went through this phase, some becoming hopeless alcoholics in the process. The starving artist became a cliché. And the idea that an artist must suffer in order to create great art (for example, Vincent Van Gogh) is now a trope.

Alcohol and drug use have played an important role in the creativity of artists. Some artists used alcohol for its power to relax and open the mind to more flexible thinking, fueling creativity. Writers like social-climbing F. Scott Fitzgerald were noted for their drinking. The ability to “hold your liquor”—to drink to excess without completely losing control–was a sign of masculinity. Novelist Ernest Hemingway’s reputation rested in part on his public persona as a hard-drinking, masculine man.

Malcolm Lowry, the British author of Under the Volcano, epitomized the trope of the suffering, alcoholic, creative genius. His novel, which has gone in and out of fashion (it’s currently experiencing renewed popularity), recounts a day in the life of an alcoholic British counsel in Mexico. Lowry weaves complex symbolism into the autobiographic dimensions of his own alcoholism.

6

My foray into the admirable ideals of consciousness-raising drug use began when I was anundergraduate. At that moment the counterculture was forming, young people were embracing the hippie values of peace, love, and personal liberation, enhanced by marijuana and other hallucinogens. Carlos Castaneda’s The Teachings of Don Juan was a must-read. Castaneda, who claimed to be an anthropologist, describes his experiences of how a Yaqui shaman in northern Mexico had led him into mystical experiences of transcendent truth by taking peyote. (Only later did it emerge that Castaneda’s books were mostly, if not completely, fiction.)

We admired Samuel Taylor Coleridge writing his poem “Kubla Khan” while high on opium. We all knew Lewis Carrol’s hookah-smoking caterpillar from the Disney version of Alice in Wonderland as we listened to the Jefferson Airplane’s injunction in “White Rabbit:”

“And if you go chasing rabbits

And you know you’re going to fall

Tell ‘em a hookah smoking caterpillar

Has given you the call

He called Alice

When she was just small.”

One pill makes you larger

And one pill makes you small

And the ones that mother gives you

Don’t do anything at all

And if you go chasing rabbits

And you know you’re going to fall

Tell ‘em a hookah smoking caterpillar

Have given you the call

He called Alice

When she was just small

When the men on the chessboard

Get up and tell you where to go

And you’ve just had some kind of mushroom

And your mind is moving low

Go ask Alice

I think she’ll know

When logic and proportion

Have fallen sloppy dead

And the White Knight is talking backwards

And the Red Queen’s off with her head

Remember what the Dormouse said

Feed your head

Feed your head

In Doors of Perception Aldus Huxley propounded the use of hallucinogenic drugs as a tool for achieving a transcendent experience for artists, intellectuals, mystics, and anyone seeking enlightenment. He drew inspiration from Meister Eckhart, Plato, Buddha, Walt Whitman, and others. Even Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, experimented with LSD, seeking to find a cure for alcoholism.

Many bohemian artists died in poverty and obscurity. They also often ended up alcoholics or drug addicts. Such information, I have discovered, is often left out of their legend. Jack Kerouac, for example, unable to deal with the commercial success of On the Road, coped through alcohol. In his last TV interview, where F. Buckley, Jr interviewed him on Firing Line, Kerouac’s alcoholism was on full, embarrassing display. He spend the last years of his life living with his mother who took care of him because he could no longer care of himself. Similarly, in Judy Garland’s final film appearance in I Could Go on Singing, she plays herself, her advanced stage of alcoholism on cringe-worthy display.

Edna St. Vincent Millay was the toast of bohemian New York in the 1920s. By the 1960s she had fallen out of favor. She grew up in poverty in Maine, but experienced the rare success for a poet of becoming a financially successful poet.

She wrote on taboo subjects such as female sexuality and feminism. She is best remembered for her poem “First Fig.”

“My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends–

it gives a lovely light!”

Indeed, Millay burned her candle bright, ending up addicted to morphine which she took for lingering pain from a car accident. She also drank heavily and ended up living in poverty and obscurity, dying from a fall down the stairs in her house in Austerlitz, NY. One scholar wrote that she couldn’t cope with “the demise of her erotic power.”

7

Frau Klemperer, my high school German teacher, opened the first door into a world beyond my imagination. She showed us “feel-good” educational films courtesy of the West German Culture Ministry. They featured beautiful Alpine landscapes, medieval castles along the Rhine, the Cologne Cathedral, and the Weihnachtsmarkt (Christmas market) in Nuremburg. We saw Trümmerfrauen (rubble women) pulling bricks out the rubble which Allied forces’ bombing had reduced Berlin to. We saw snapshots of the rapidly rebuilt cities of the West German Wirtschaftswunder.

I zeroed in on West Berlin. Frau Klemperer and her husband had been university students in Berlin the 1920s. She spoke in rich details about her life in the wonderful, terrible “golden twenties” world of Weimar Berlin. The trauma of losing World War I and the disaster of hyperinflation caused by France’s insistence that Germany pay for that war fed the thriving cultural experimentation in Berlin. This included the tolerance of homosexual men and women living openly and safely. Much later on I would learn that the readily available young men for gay sex, as documented by Christopher Isherwood in The Berlin Stories, were usually turning to prostitution as an antidote to poverty.

We also learned about the heyday of Weimar-era German filmmaking. There was the sex symbol Marlene Dietrich in the role of Lola Lola leading high school teacher Professor Unrath (Emil Jannings) down a path into social disgrace and insanity.

(In the 1960s we still shared the collective cultural memory of Dietrich and recognized her signature song “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt,” which she sang in English as “Falling in Love Again.”) The critique of capitalism in Berthold Brecht’s Dreigroschen Oper (Three-Penny Opera) was lost on us. We were living the Disney version of postwar America as the best of all possible worlds. We had no collective memory of Lotte Lenya. Even as Bobby Darin was topping the charts, singing “Mackie Messer” translated into English as “Mack the Knife.” I thought Bobby Darin was the pinnacle of cool, so much so that I had my first wet dream imagining myself having sex with him under the football bleachers.

We were taught that prior to Hitler Germany had been celebrated as das Land der Dichter und Denker (land of poets and philosophers). We learned about Goethe, Schiller, Kant, Hegel, and Nietzsche. We read excerpts from Hermann Hesse and Thomas Mann. (The Magic Mountain was a bestseller in the US.) I was particularly taken by Franz Kafka.

Encouraged by the signs of my intellectual interests and capabilities, Frau Klemperer nurtured my passion for German. She tutored me in fourth-year German while I was taking third-year German. She saw to it I was honored with the West German Award for Excellence in my junior year, an honor reserved for graduating seniors. She encouraged me to correspond with pen pals in Germany. She encouraged me to apply to be an exchange student to West Germany. This became my most fervent desire. For a working-class country bumkin this was heady stuff.

8

When I was 13 the concept of coming out of the closet did not yet exist, and I could not know there was a life “that was out there waiting for me all along.” In The Sound of Music novitiate Maria (Julie Andrews) is torn between her call to serve God as a nun and her burning desire to marry the man she has unexpectedly fallen in love with. “Climb every mountain,” her Mother Superior advises her, “follow every rainbow, till you find your dream.” This song still tugs at my heartstrings, stirring a longing to come home to my dream.

Like many of the gay men of my generation, I looked to the movies for clues to make sense of the incongruous parts of my life. So many of us longed for a Technicolor world like Dorothy Gale. “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” has been our collective anthem and San Francisco our Oz. Like little Patrick Dennis we also wanted our own Auntie Mame, who would love us just as we are and open doors to us, doors we never dreamed existed. In the beloved Billy Wilder camp vehicle Some Like It Hot Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis dressed in drag pursue Marylin Monroe. The film closes with the Jack Lemmon character being whisked off to marriage with the Joe E. Brown millionaire character. In one of the most famous closing scenes, Brown blithely refuses to be put off by Lemmon’s revelation that he’s a man. Ever accommodating, Brown declares, “Nobody’s perfect.”

In Breakfast at Tiffany’s the “real phony” Holly Golightly (played by Audrey Hepburn) has escaped her hillbilly child marriage to reinvent herself in New York City. She rejects love, declaring that people don’t own each other. In spite of herself, she falls in love with her soulmate (played by George Peppard), who gives up being kept by an older woman to pursue Holly. This film closes on a schmalzy note, Hepburn and Peppard in the pouring rain, embracing Holly’s orange tabby “Cat.” She had thrown “Cat” out of their taxi, a symbolic act of rejecting romantic “ownership.” Mildred Pierceand All About Eve also spoke to a gay sensibility, but in a much different register.

I will always be deeply grateful to Frau Klemperer for opening my first door and pointing me in the direction of the life I never could have imagined. “You have to live the life you were born to live.” Like Christopher Isherwood eventually had to admit to himself, “I am a social and sexual creature.”

9

Gay artists of a bohemian bent, such as Christopher Isherwood, John Rechy, and John Waters, were not yet on my radar. With the exception of Oscar Wilde, there was not yet a tradition of homosexuals being famous for their homosexuality.

In 1972 when I was an undergrad in Albany I read Hermann Hesse’s novel Steppenwolf, with its striking depiction of a jazz subculture that included drug use and free love. The protagonist Harry Haller is seeking an escape from his stultifying bourgeois life. One night he sees the entrance of the Magic Theater. It is a street he has walked down many times and has no explanation for the mysterious emergence of the Magic Theater. He meets the bisexual jazz musician Pablo who serves as his guide into this bohemian world. I did not know of the existence of bohemian bars or gay bars. But I found the intimations of such a place electrifying.

When I first walked into G.J.’s Gallery, a neighborhood bar in Albany’s bohemian Lark Street neighborhood, I found my Magic Theater. It was dark, filled with cigarette smoke and the smell of grass. The Rolling Stones played on the jukebox. I quickly became familiar with the bar’s clientele: writers and painters from the neighborhood, some drug pushers, some gay men, and the occasional college student like me, who could frequent bars when New York State’s legal drinking age was 18. The crowd was almost exclusively men–some smoked joints in the bathroom and dealers peddled acid, speed, Quaaludes, and grass in the back of the bar out of view of the bartenders.

Freshman year I had a girlfriend. She was my only female lover. She took me to a reading by poet Robert Duncan, who was openly homosexual. I began to look for clues of gayness in other contemporary poets. By my senior year I had come out of the closet, was living with my first gay lover, and we were both self-styled poets. Through him I encountered gay poets who wrote more or less openly about their homosexuality—C. P. Cavafy, Frank O’Hara, Jack Spicer, John Wieners, Allen Ginsberg. Some wrote about their bouts of madness and their poverty—their precarity and their nonconformity. True to the bohemian spirit, Spicer considered fame anathema to artistry, and even denounced Ginsberg’s “Howl” as “crap” because of its fame. Spicer died in the poverty ward at San Francisco General Hospital in 1965.

They say, those who wander are not lost. As I accumulated ideas from studying literature and reading up on the lives of authors who intrigued me, as I put the countercultural values of my generation into practice, as I experimented with alcohol and drugs, as I explored my “deviant” sexuality first in secret and then openly, I found myself embarking on my own “hero’s journey.” I became a gypsy-scholar, a grassroots gay activist, a sexual adventurer—I derived meaning for my life through my bohemian quest to experience and write (to echo Christian in Moulin Rouge) about “truth, beauty, freedom, and that which I believed in above all things: love.”

Joseph Campbell asserted that “the hero’s journey” is mostly misunderstood.

People assume the hero’s journey is about facing and doing battle with your fears. Think of Sam Lowry in Brazil escaping a meaningless life in a totalitarian society by escaping into fantasy. In this version of the hero’s journey Lowry battles a giant samurai to free enslaved people. Upon slaying the samurai, he rips off the mask only to see his own face. The same trope appears in the Star Wars films, where Darth Vader, whom Luke Skywalker has been trying to slay, turns out to be his father. The dragon these heroes slay turn out to be the dark side of themselves.

Paul Weinfield has pointed out that in reality the dragon slays you. Our belief that the goal in life is to win only sets us up to fail and to abort our journey and to set off on another journey and another and another. We are thereby set up for failure and heartache over and over. If you let yourself be shattered, realizing that you have been at war with yourself, and not with the world that didn’t want the gifts you had to offer or the dreams you hoped to realize, then your transcendent life begins. “Every defeat is just an angel,” as Weinfield writes, “tugging at your sleeve, telling you that you don’t have to keep banging your head against the wall.” Kafka’s protagonists never give up banging their heads against the wall. Perhaps Kafka was wise to this transcendent truth and that may be why he found his tales humorous, instead of tragic.

10

Bohemianism has undergone a drastic transformation. In recent decades it has bifurcated. We can trace the commitment to artistic authenticity, often, but not always, as typified by a life lived in obscurity and poverty. Avant-garde artists, the Beats, dharma bums practicing Zen Buddhism, gypsy wanderers all created their own bohemian communities. But there is another, more recent, tradition of bohemianism, which began with the “dandy.” A dandy was poor but dressed well in order to appear rich. Bohemian circles occasionally had a wealthy member or patron, whose money made their lifestyle sustainable.

In recent time rich eccentrics have been joined by affluent hipsters. Their taste for boho-chic fashion has coopted and commodified bohemianism, turning it into a look, introducing it into the culture industry of mainstream capitalist society. As the economic divide between the “haves” and the” have-nots” has widened in the 21st century, a new precariat underclass has emerged. While the well-heeled in the high-tech world dress in boho chic, many other young workers—not just artists and other creative types–now lead precarious lives as a living wage and job security have been evaporating. I know that lifestyle well, having pursued a career as a humanities academic, working most of my adult life in a field with few stable, remunerative, full-time positions and unable to find steady full-time employment outside of academe.

11

Even as a small child I have known moments of being engulfed by an unnamed, unnamable longing. Before I had words for this longing– a mix of inchoate dreams and mysterious physical desires–I had glimpses of it. It was the world I saw it in Bell, Book, and Candle. I saw it in Shangri-la in the film Lost Horizons, a harmonious paradise high up in the Himalayas, where people aged very slowly and lived in perpetual peace. The Four Coins’ pop song “Shangri-la” underscored the emotional magic of such a place, the place that only romantic love could transport you to.

In high school we studied “Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood,” by William Wordsworth, a Romantic English poet. I found my own childhood desires echoed, desires for a beautiful place where love, peace, personal and sexual fulfillment converged–a place where I would truly belong

My best friend Tom and I were also, for lack of a better term, secret lovers. We had met in the Boy Scouts and became best friends. We also engaged in adolescent sex play that blossomed into regular weekend sleepovers, Boy Scout camping trips, and summer afternoons stripping our clothes off in the woods and having naked sex in a secluded meadow under the sun. We guarded our secret carefully. No one questioned our devotion as best friends. But I longed for a world where we could be open. Doris Day sang about this in “Secret Love”–

Now, I shout it from the highest hills

Even told the golden daffodils

At last my heart’s an open door,

And my secret love’s

No secret anymore.

The sexual and cultural revolution of the 1960s spread into the most remote corners of America. The Broadway musical Hair celebrated this youth revolution This incarnation of bohemia was arriving via mass media. We became guitar-playing folk singers and hippie poets. Some of my classmates began defying the dress code and wore jeans and tie-dye tee shirts to school, let their hair grow long—detention had no effect. A few of us even began smoking marijuana.

I saw Auntie Mame for the first time when I was five years old. Mame (in Rosalyn Russell’s incomparable interpretation) opened doors gay men of my generation never even dreamed existed. Through her breezily unconventional lifestyle and unflappable nonjudgmentalness she showed us how to survive and thrive in a world where people like us were not supposed to exist. What gay boy wouldn’t want the unconditional love and guidance of such an adult guardian? But where in the real world would such longings be fulfilled?

Mame Dennis appeared to have or find the money necessary to maintain her bohemian lifestyle. She supported artists and the film ends with her becoming a published writer. Although her nephew Patrick is portrayed as heterosexual. He becomes engaged to a vacuous upper-class debutant. But he meets and falls in love with an interior decorator who was apparently destined to be his life partner. He ends up with a wife who will fit with his bohemian upbringing. The real-life author of Auntie Mame, who used the pen name Patrick Dennis, was a gay man.

12

All these things I longed for–my own gay Berlin, my own community of fellow bohemian writers, poets, artists, political activists, intellectuals, spiritual truth-seekers, gypsy-scholars. (To date, I have lived in fourteen different cities and have moved around within many of them.) I have experienced these communities for periods of time.

I continue to seek the gay bohemia I have had glimpses of. I found a home in San Francisco’s Castro District. When I moved there it was at the height of jubilant gay liberation, epitomized by living openly and having as much sex as possible. We celebrated the very thing that we had been marginalized for. The advent of the AIDS epidemic, seemingly killing us for the very thing we had been stigmatized by, turned our joyous lives into sorrow and profoundly changed gay community forever.

I found a home in the warm and welcoming fellowship in gay AA in San Francisco. We were welcome in regular AA, usually provided we did not mention our homosexuality. As a result, we created our own fellowship. Living with the trauma of homophobia, a major factor for most of us turning to excessive drinking and becoming alcoholics, we needed to have no secrets and to talk openly and honestly about our gayness in order to recover and to achieve long-term sobriety. In the early 1980s gay AA was flooded with newcomers hoping that sobriety would save them from AIDS. However, AIDS killed the majority of us. AIDS killed much of the twin joys of gay liberation and new-found sobriety. The fellowship was decimated. Many struggled to stay sober in the face of an inevitable, fast-approaching, horrendous death. We were overwhelmed by grief and the never-ending process of burying our brothers. That home came and went.

I found a home in the early bear community, which came into existence, in part, as a positive response to the AIDS epidemic. When bears became mainstream, the spirit of a nonjudgmental democratic community was replaced with a social hierarchy, with A-list and muscle bears driving out that original spirit. That early community has come and gone.

I have moved in various gay intellectual and academic circles. Most of us had begun as gay activists with left-leaning social values. Over time such circles, such as the San Francisco Gay and Lesbian History Project, collapsed as we found employment in the academic world. Unlike me, most of them went on to become important, influential, financially well-off, respectable, seminal historical figures. In this case, I remained firmly stuck in bohemian poverty. I only realized this when I took a retrospective look at our divergent paths. That community also came and went for me.

The one bohemian community that has remained a constant in my life has been the Billys, a heart-centered gay men’s community akin to the radical faeries,. We come together in a spirit of honesty, vulnerability, and joyful creativity through

intimate heart connection.

Having been an outsider most of my life, in part by choice and in part by social exclusion, I have paid a huge price. As Jacques Barzun once wrote, “Artists feel the lure—no, the duty—of joining an adversary culture; for the artist is by nature ‘the enemy of his culture.’”

I recently learned the Welsh word for the longing I had for this place, my bohemia–“hiraeth.” Pronounced “HEE-ryth,” this word names a feeling akin to “homesickness.” Like homesickness, it is a longing for a place, but unlike “homesickness,” it is a longing for a place you have never been to, a place you can never go to, and, frequently, a place that has never actually existed–because it is a place that can never be. I have mixed feelings about where I stand on the merits of bohemians who have found success which has lifted them out of poverty and those, like me, who have remained in bohemian poverty. I have finally made peace with my fate and now take great joy in my own private bohemia, living in my well-appointed artist’s garrot with my cats. I am pursuing my intellectual and creative passions, free from the need to please anyone else. Looking back I now value the journey and the hope that has propelled me forward, even through the darkest times. I take as my own Edith Piaf’s anthem to the life she chose to live–“Je ne regrette rien.”